What is GDP? And How Does It Reflect the Level Of Economic Activity?

Gross domestic product (GDP) from a professional Independent perspective can be viewed as a macro-level diagnostic tool. GDP is the primary metric used to measure the size and health of a nation's economy. Gross domestic product (GDP) was a solution designed to address a specific information gap: the government's inability to quantify its own economic strength during a crisis. The modern concept was first developed by Simon Kuznets, who was a Russian-born American economist and statistician in the early 1930's.

The problem: During the years of the Great Depression (1929-1939), the US government struggled to respond effectively because it lacked comprehensive data on the total value of goods and services produced.

In 1934, Kutzet presented a report to the US Congress titled National Income 1929-1932. The report established the first national quantitative framework for measuring a nation's economic output. While Simon Kutzet laid the groundwork for GDP, the concept was refined and standardised globally following the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which established international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank.

Who Uses GDP?

GDP is a high-leverage tool used by various stakeholders to use data driven decisions. Governments and central banks use GDP to determine tax revenue projections and decide on public spending (e.g. infrastructure or social programs). Central banks like the (federal reserve) monitor GDP growth to decide when to raise or lower interest rates to control inflation or stimulate a sluggish economy. GDP is the scoreboard by which political leaders are often judged by the electorate. The IMF and the World Bank use GDP to assess the economic stability of countries, determine eligibility for loans and allocate international aid. Inclusion in elite groups like the G7 or G20 is largely determined by a nation's GDP.

An Independent Professional Consultant may use GDP data to advise clients on which markets are growing and where consumer purchasing power is increasing. High GDP signals a healthy business environment, encouraging corporations to hire more workers and invest in new capital. Financial markets rely on credit ratings from agencies like Moodies who use the Debt -to-GDP ratio to assess a country's ability to pay back its sovereign debt, which directly influences the interest rates a country must pay.

In business and governance, GDP is more than just a static number; it is a dynamic signal used to synchronise operations with the broader economic environment. These organisations treat GDP as a sensor that helps them emphasise with market conditions and prototype their future strategies. For example, large firms like McDonald's and Unilever use GDP as a segmentation and allocation tool. They analyse GDPper Capita to determine the Affordability Threshold. A company like Unilever might look at a company's GDP growth to decide whether to launch a premium product line or sachet marketing (small, affordable portions) in emerging markets. If a country's GDP is stagnating, a consultant would advise shifting defensive capital to more robust regions to maintain shareholder value.

In the financial sector Investment banks and Hedge Funds like like Goldman Sachs and BlackRock use GDP for determining the asset value compared to other assets. This is known as Relative Valuation. They also use GDP for comparing a country's Debt-to-GDP ratio. Analysts use this ratio daily to price sovereign risk. If a nation's debt grows significantly faster then it's GDP, the bank may downgrade that country's credit rating, making it more expensive for that country to borrow money. This creates a feedback loop; a high debt-to-GDP ratio can lead to Capital Flight, where investors pull out of a country, further slowing its economy.

Retail Giants like Walmart and Amazon use GDP as a predictive proxy for consumer behaviour. They track inflation-adjusted GDP to forecast discretionary income. If GDP were predicted to dip, a retailer might reduce orders for luxury electronics and increase stock of essential private brands. This aligns with the Lipstick effect - the theory that during economic downturns (indicated by low GDP), consumers spend less on big-ticket items but more on small, affordable luxuries to maintain a sense of well-being.

How GDP Reflects Economic Activity

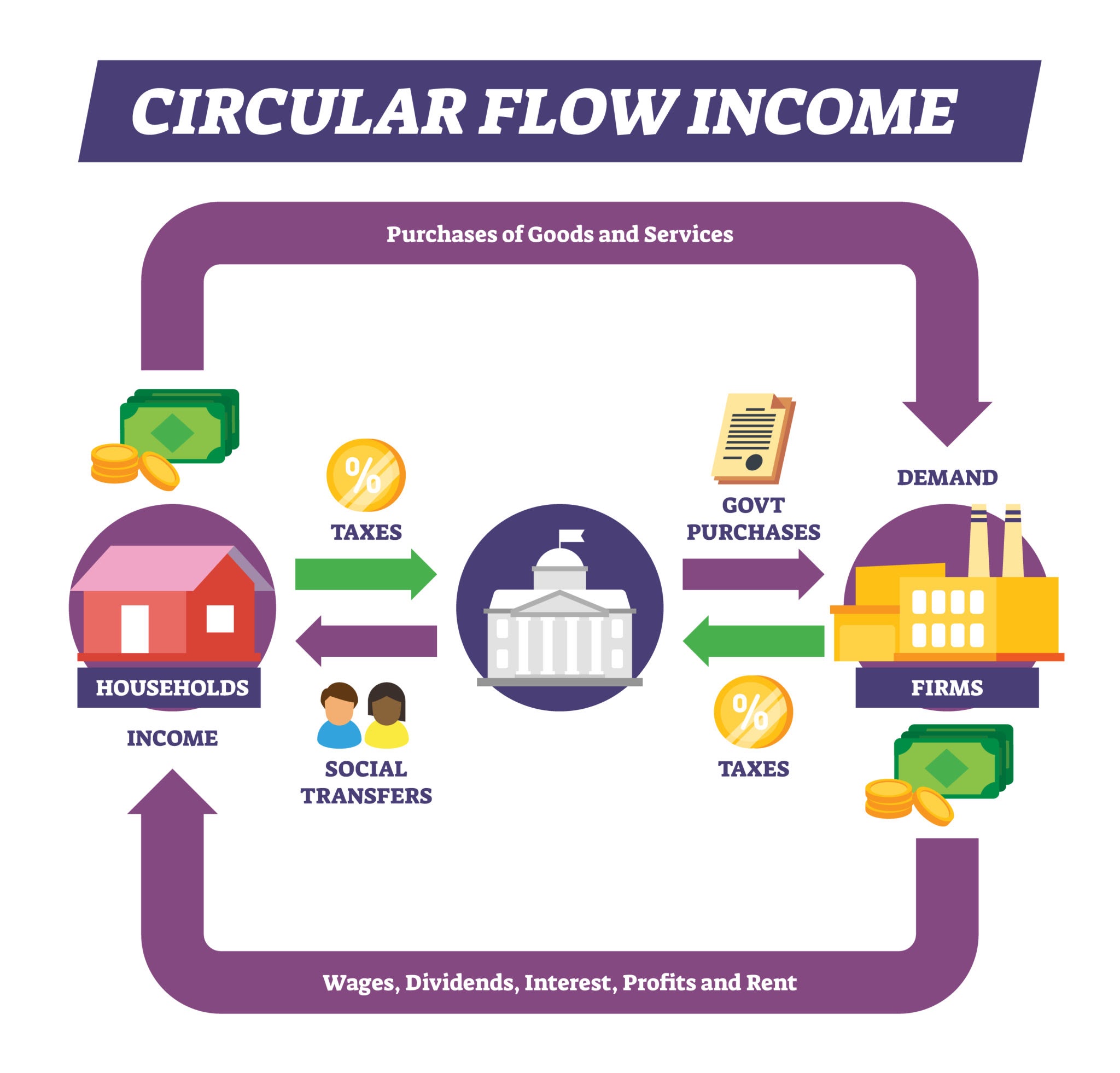

From a psychological standpoint, GDP functions as a social proof mechanism. High GDP growth signals success, which increases consumer and investor confidence. This leads to more spending and investment, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of growth. Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP (a technical recession) trigger a scarcity mindset. Businesses freeze hiring, and consumers stop spending, often worsening the downturn due to fear rather than a fundamental lack of resources. GDP measures the total metabolic rate of an economy. It captures the flow of value through three primary approaches:

The Expenditure Approach (demand) sums up all spending: GDP= C+I+G+ (X-M). This reflects the appetite of the market, how much consumer C businesses (I) and Governments (G) are willing to invest.

The Income Approach ( Reward): Adds up all the income earned from production(wages, rent and profits). This reflects the sustenance of how much money is actually landing in the pockets of workers and shareholders.

The Output/Production Approach (Supply): Measures the value added at every stage of production. This reflects the productivity and efficiency with which resources are converted into finished goods.

When real GDP (adjusted for inflation) increases, it signifies that more value in transactions is occurring. This is the hallmark of a healthy economic ecosystem where the circular flow of money is increasing.

How changes in economic activity affect business organisations

Fluctuations in economic activity create a ripple effect that forces organisations to change their business activity. High GDP (Expansion) creates a fear of missing out (FOMO) in boardrooms. Businesses become risk-loving, leading to aggressive hiring, increased R&D and expansion into new markets. Low GDP (Contraction): triggers loss aversion. Even if a company is currently profitable, a dip in national GDP can cause a hunker-down mentality, resulting in budget freezes and workforce reductions.

From a consultant's perspective, a change in GDP is a problem-framing opportunity. Instead of reacting with fear, a business should use the following design-led steps: Emphasise: During a GDP dip, your customers Pain Points change. They aren't looking for luxury, they're looking for certainty and cost savings. If GDP is falling, the constraint is no longer how do we grow? But how do we provide the most value per pound spent? Ideate and Prototype. Create a low-cost version of your products to keep cash flow while the economy resets. Then launch small-scale recession-proof marketing campaigns to see if the new value proposition resonates before a full-scale pivot. The most successful organisations use economic downturns (negative GDP growth) to stress test their value proposition. Companies like Netflix and Airbnb thrived or were born during economic shifts because they solved new problems created by the change in economic activity.

Strategic Limitations (The Consultant's Critique)

While GDP is a powerful metric, it has significant blindspots that a professional consultant should always highlight. The Broken Window Fallacy: GDP measures economic activity, not necessarily value. If a hurricane destroys a city, the rebuilding effort can increase GDP, even though the nation is arguably worse off. GDP ignores unpaid labour (childcare, housework) and the informal economy (cash-in-hand work), which can be massive in developing nations. Quality Vs Quantity: GDP measures the size of the pie but not the distribution of the slices (inequality) or the quality of life, happiness (health, happiness, environment). GDP is a measure of Market Throughput. It tells you how fast the engine is running, but it doesn't tell you if the car is headed in the right direction.

Conclusion: Navigating the Map, Not the Terriority

In the landscape of global commerce, GDP remains our most robust "Macro-Diagnostic" It provides a vital pulse check on the collective output of a nation, serving as the primary benchmark for market size, investment viability, and fiscal health. However, for the modern leader, the value of GDP lies not in the actual number, but in the psychological and structural signals it broadcasts to the market. As we have explored, a rising GDP is more than a statistical gain; it is a catalyst for consumer confidence and a trigger for capital expansion. Conversely, a contracting GDP often initiates a "scarcity mindset," where the collective fear of recession can become just as economically damaging as the fundamental downturn itself. To lead effectively, one must look past the noise of the headline figures and analyse the underlying mechanics of growth.

Professional Checklist for Strategic Leaders

1. The Real Filter: Always distinguish between Nominal and Real GDP to ensure your growth projections aren't being masked by inflationary pressure.

2. Sectoral Precision: Use granular tags to identify exactly where the momentum lies within your specific industry.

3. The Value Gap: Acknowledge that GDP measures throughput, not sustainability. High output without quality or social resilience is a fragile foundation for longterm business strategy

Ultimately, GDP is a map, not the territory. It is an indispensable tool for orienting your organisation toward opportunity, but it must be balanced with human-centric insights to fully understand the future of the market.

Master the Macro: Are you reacting to the economy or anticipating it? Understanding the "Why" behind is the first step to resilient leadership. If you're looking to transform these high-level economic insights into a tailored strategic roadmap for your business, I invite you post in the community forum or contact us via email. Let's move beyond data and start creating your competitive advantage.